“Colonization” and “decolonization” are hot topics these days. You can hardly set foot in an Anglo-American or European classroom, book store, or museum anymore without some leftie lecturing you about the need to “decolonize” everything in sight. Well, I always like to give people a fair hearing, so I figured I it was worth taking a deeper dive into the topic of colonialism in order to broaden my understanding. And it turns out that those folx may be onto something! I am now woke to colonial injustice, and even won over on the urgent need for decolonization. Though maybe not in quite the way they’d assumed. So please glue yourself to the floor and join me for an educational lecture on the enduring relevance of the colonial menace.

Let’s begin with a summary of the core aspects that have historically defined colonialism and colonial rule, as I’ve distilled here from the many decades of study and writing that have been conducted on the topic (mainly by left-wing scholars):

De-nationalization: Colonization proceeds hand-in-hand with empire and imperial rule. An empire is defined and distinguished from a normal nation-state by its exercise of domineering control over many different nations, or peoples, within a single political entity. This control may be direct, with the empire occupying and annexing these nations’ traditional territory. Or it may be indirect, with the empire allowing nations under its control to govern themselves mostly autonomously but demanding their tribute and fealty to its ultimate authority. The antithesis of empire is national self-determination, or the ability of nations large or small to fully rule themselves independently and to determine their own destinies without interference from above and abroad. Which is why, during the last great wave of decolonization that swept the world in the decades after WWII, the struggle for national self-determination was practically synonymous with anti-colonial struggle (and democratization). Hence a chief task of any determined colonial ruler is often de-nationalization, or the suppression or erasure of a ruled population’s conception of themselves as a coherent people with a distinct cultural identity and a delimited historical territory.

Division: As an aid to suppressing national self-determination, empires have very commonly utilized a particular “divide and rule” strategy: setting up one or more sub-national ethnic, religious, or other minority groups to rule over a local majority population. This minority-rule system works well for an empire, as the minority group then owes its position of power and privilege to imperial authority, and – fearing what it might lose if the national majority were ever allowed to rule – is therefore understandably far more loyal to the empire than to the nation in which they reside. The minority then also has an incentive to collaborate with the empire’s effort to de-nationalize the majority. The majority, for its part, often soon grows more and more resentful of the minority. E.g. the Belgians infamous use of colonial Rwanda’s Tutsi tribal minority to rule over its Hutu majority led to the buildup of explosive grievance politics and eventually genocide. But generally the empire is fine with the growth of this kind of anger: it would much rather a national majority’s rage be directed at a local scapegoat than the empire itself.

This was the general strategy famously employed to great effect by, for example, the British Raj in India and the French in Syria and Lebanon. But it was hardly a European innovation, having been used by various empires for millennia. The Ottoman Empire’s “Millet System,” for example, was a system of “multi-cultural” imperial administration, in which religious and ethnic minority groups across the empire were granted autonomy and even special privileges – to such a degree that official recognition as a minority group became something of a prized status for which various groups would actively lobby the Sultan.[1] The Ottoman elite would then tap these loyal minorities for administrative and military talent. This helped keep their expansive empire relatively stable for centuries.

Deculturalization and Demoralization: Deculturalization is the process of stripping a people of their traditional culture, customs, beliefs, values, and language, and forcibly replacing these with those of a new dominant group. Unlike acculturation or assimilation, which is an individual’s choice to join an existing dominant culture, deculturalization is a coercive process waged from the top down. It involves the deliberate severing of historical roots and abolition of historical memory, including through censorship, propaganda, indoctrination, and desacralization. For practical reasons, deculturalization’s primary target is usually children, whom the colonial regime aims to isolate and reeducate so that they become an entire generation left with no knowledge of their independent past or any sense of their traditional identity. In some cases in history colonial regimes have gone so far as to regularly remove children from their native parents in order to raise them entirely within the colonial culture.

Often, deculturalization is accompanied by a concerted campaign of deliberate demoralization, or the attempt to convince a people that everything about their culture, ways of life, or race as a whole is inferior, backwards, and barbaric, and that they would be better off adopting the cultural values and ways of life of their colonial masters, who are obviously their civilized betters. In fact the whole process of colonization may be presented as (and even genuinely seen by the colonizer as) a beneficent civilizing process. Sometimes, however, demoralization is more purely literal and direct, and intended less to convert than to merely pacify by any useful means. When the British Empire managed to hook large swathes of the Chinese population on opium, leaving them addicted, dependent, and literally passed out in drug dens, this was a highly successful means of pacifying them and undermining any energetic resistance to colonial exploitation.

Displacement and Dispossession: Of course, the cultural dispossession of a people is usually also accompanied by an economic and physical dispossession. What was once their property is, gradually or all at once, taken from them and redistributed to the colonizers and their privileged elite groups. This may involve the removal of the people from their land, including by forced migration, or simply by policies that make it, over time, more and more economically impossible for them to retain ownership. Obviously uprooting a people from their traditional land is also beneficial to the colonizer’s effort to denationalize and deculture them.

But sometimes this displacement is more thoroughly completed through another means: the deliberate mass inward migration of an outside group (either the colonizer population themselves or a chosen minority group) into the lands of the colonized in order to reduce their demographic and cultural majority, undermine their control of land and resources, and weaken their political voice. This is a strategy that the People’s Republic of China, for example, has used quite successfully in Tibet and Xinjiang, where it has transferred millions of Han Chinese settlers in to dilute the local ethnic populations. In the most severe cases, when inward migration is combined with efforts to actively reduce the population of the native group over time, such as through the suppression of their fertility, this strategy is today internationally recognized as a form of genocide.

At the broadest level, displacement and dispossession is about more than just material theft. To the natives, it is a whole way of life that is taken from them and permanently replaced with something alien, unrecognizable, and entirely unasked-for. At its worst, it means that not only their way of life, but they themselves are doomed to be replaced – reduced to ruins, artifacts, and myth in their own former homeland.

Exploitation: Meanwhile, at a day-to-day level, colonization is characterized by one form or another of the exploitation of the native people and their land by the colonizer. This often includes the strip-mining of the nation’s various resources to ship aboard, with the profits flowing to the colonizers rather than benefitting the people of the nation. There often appears, however, a class of natives quite willing to sell out their nation by helping to facilitate its exploitation in exchange for wealth and status lavished on them by the colonial empire; these collaborators are known as “compradors,” or the native agents of a foreign power. Often the empire also deliberately subverts the colonized state’s local industries, or prevents their emergence, so as to reduce any competition that could potentially threaten its own international economic monopolies. Financial methods are also often used to exploit the nation and its people, trapping them in a complex web of inescapable debts. Naturally, colonial exploitation typically includes the direct exploitation of native labor, working them hard to produce profits without fair compensation (or any compensation). Occasionally the natives are conscripted as military cannon fodder and sent abroad to fight the empire’s foreign wars. At their most sophisticated, empires cleverly strip-mine the native population themselves as a human resource, sucking up the brightest and most promising natives and draining them away to other nations or metropolitan capitals to be reeducated and coopted into serving the trans-national imperial system.

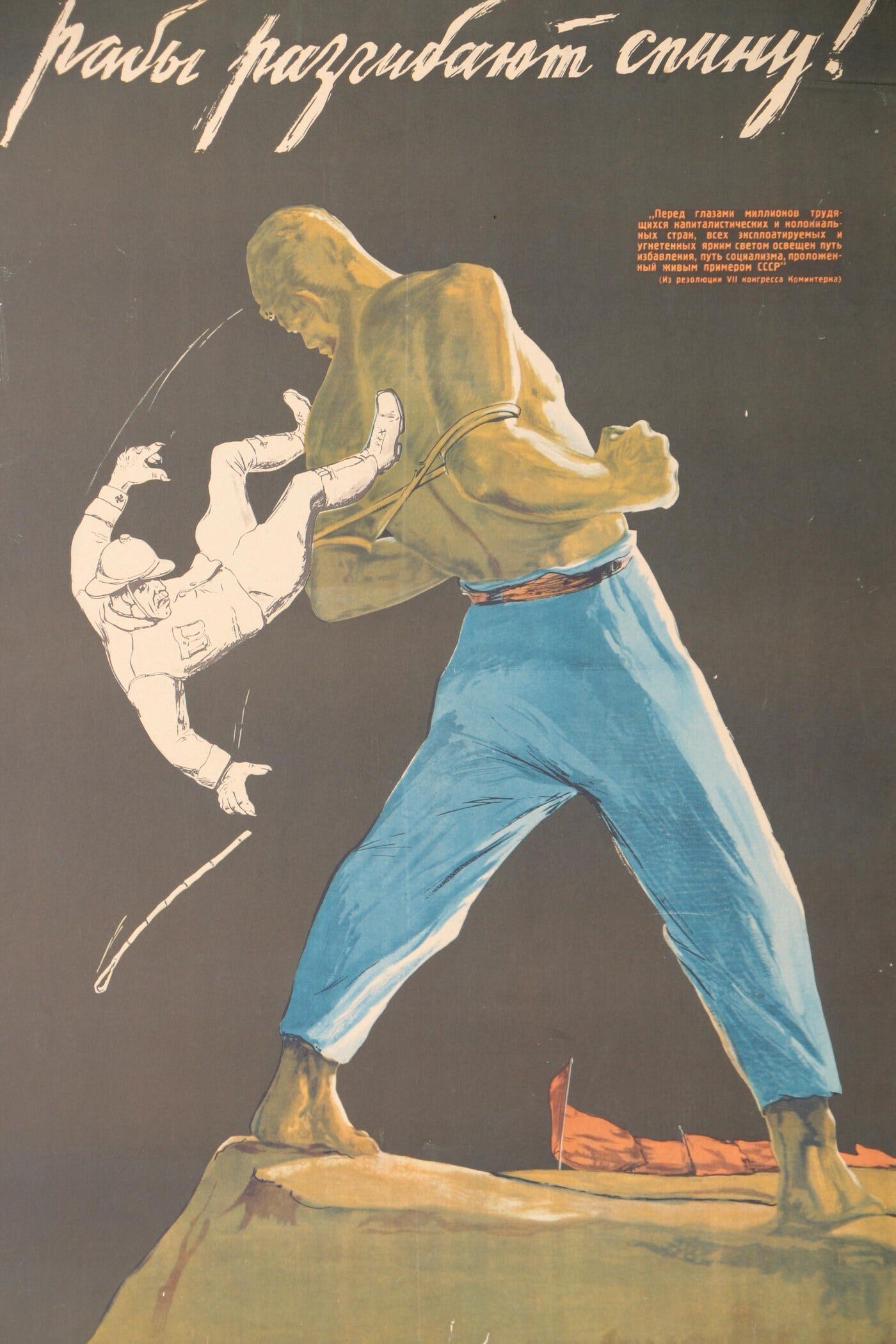

Enforcement and Systemization: Of course all this exploitation and dispossession tends to make the natives angry and liable to try to revolt and throw off the colonial yoke, so the colonial power must establish a strict system of enforcement and protect its control over the local majority. Secret police, surveillance and censorship, restrictions on freedom of association, sturdy black-box prisons, and the occasional massacre of uppity rebels/protestors usually do the trick. Fear will usually keep the local systems in line.

But there is a more subtle and comprehensive means of control that works effectively too: the systemization of imperial authority and its bureaucratic administration into an all-consuming “rule by law” managerial apparatus that is deliberately complex, elevated, distant, and almost wholly inscrutable to the native. Proceeding hand-in-hand with the campaigns of demoralization, the native is made to feel that decisions about his nation and even his own future are something simply out of his hands – something to instead rightfully be handed down by his far-away betters like declarations dispatched from the heights of some unseen Mount Olympus. In this way he is conditioned to assume that to challenge the vast machine of the empire would be impossible, pointless, and against the whole inevitable tide of civilization.

The Over-Empire

That then is roughly what colonialism has looked like wherever and whenever it has reared its ugly head over the centuries. But, maybe all this history sounds a bit, well… uncomfortably familiar to you, dear Western reader? Perhaps, reviewing its characteristic deprivations, you even suspect that this ravenous beast could actually be the very same one that seems to be devouring you piece-by-piece this very moment?