Hard Lessons from Israel’s High-Tech Border Failure

Thoughts on complex systems, failure cascades, and the international order

Over the last two weeks I have, like everyone else, been closely following Hamas’ horrific attack on Israel and the resulting war. So many others have already done an eloquent job covering it at a general level that I’m not going to try to do the same, however. There is one specific aspect to the whole (ongoing) story, though, that I am keen to return to and focus on in brief here, in part because I see it as directly relevant to some of the core themes I’ve been trying to think through for some time now. That is the total failure of Israel’s extremely expensive, high-tech Gaza border defenses to stop the initial surprise attack by Hamas.

I’ve seen a surprising number of people, on both Right and Left, argue or imply that the swift collapse of these supposedly impenetrable defenses, along with the subsequent very slow response by the Israeli military to the attack, in itself justifies a conspiratorial explanation – e.g. that Netanyahu, or Washington, or whomever on the inside must have wanted the attack to get through, as otherwise it couldn’t have gotten through. I find this idea ridiculous, and telling. Telling in that many apparently find the notion that Israeli Jews were deliberately betrayed and allowed to be murdered by their own fiercely nationalist government to be a more readily believable theory than that complex technological systems could possibly fail. I think this fact speaks to something important about how we moderns have come to misperceive how things work, misplace our faith in systems, and often accidentally make ourselves more rather than less vulnerable to chaos.

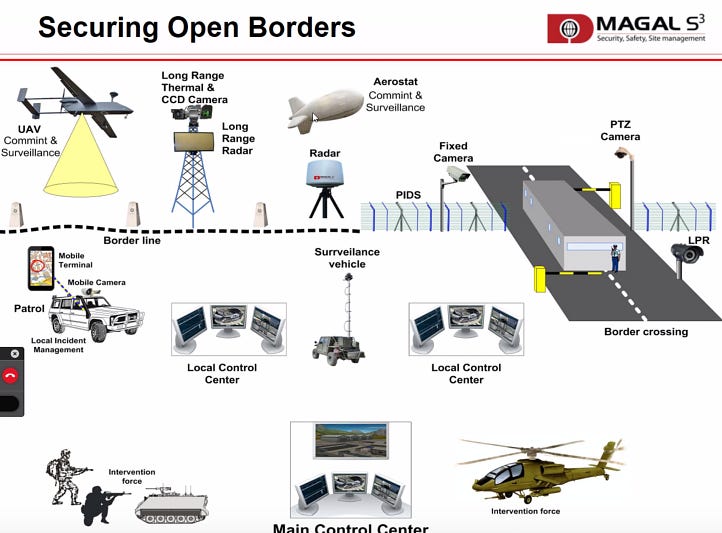

Over the last few years, Israel spent more than $1.1 billion USD to construct a sprawling security barrier along the entirety of its nearly 40-mile border with Gaza. This was, allegedly, to be the fence to end all fences. In addition to 20-foot high multi-layered wire, steel, and concrete barriers, the “smart fence” integrated a vast network of cameras, motion and other sensors, radars, and remote-controlled weapon systems, all monitored by dozens of towers that served as data hubs and high-tech observation- and listening-posts. An underground wall and sensor system, designed to stop infiltration by tunnels, was extended far below the earth along the whole border, at great expense. Meanwhile Israel’s advanced, exceptionally costly “Iron Dome” missile defense system protected the skies.

“This barrier, a creative, technological project of the first order, denies Hamas one of the capabilities that it tried to develop and puts a wall of iron, sensors and concrete between it and the residents of the south [of Israel],” then-defense minister Benny Gantz declared at a ceremony marking its construction in 2019. “The barrier is reality-changing. What happened in the past won’t happen again,” then-IDF chief of staff Aviv Kohavi added.

Some former members of the IDF who served on the border have in recent days testified on social media that the fence really was a technological marvel. Not so much as a stray cat could get anywhere near the border without setting off alarms, they recall. And the government and military certainly seem to have believed it was indeed impenetrable and really had changed the reality on the ground; hence partly why, by the start of this month, they had redeployed most of their regular military forces to guard the West Bank and northern border instead.

But of course on the day of action this great wall of silicon proved almost totally useless, overcome in a matter of minutes by Hamas, which was then left to rampage across Southern Israel almost unopposed. At least 1,400 Israelis lost their lives as a result. What happened? Let’s lay aside Israel’s broader strategic intelligence failure (having been falsely convinced that Hamas had been successfully pacified and was no longer interested in attempting attacks), which this certainly was. The border’s defenses were in themselves supposed to be able to detect and repel even an unexpected assault – or at least were billed as such. How and why did they fail?

According to initial reports of what happened on the day of the attack, Israeli signals intelligence did in fact notice an unusual spike in activity immediately ahead of time and sent an urgent alert to the border, but this was either unnoticed, ignored, or not recognized as a serious concern. While I was not there and certainly can’t say for sure why this occurred, it isn’t hard to imagine many run-of-the mill possibilities: it was a major Jewish holiday and many soldiers had been granted leave to go home, so the staff typically responsible may have simply been absent; we also know that the soldiers were right in the middle of a shift-change, which Hamas probably easily observed and timed, so the alert may have been missed; or perhaps whoever would normally have dealt with the message was just busy eating breakfast, had received many similar alerts in the past that turned out to be false alarms, and thought that dealing with it could wait a few minutes. In other words, ordinary human error seems overwhelmingly likely to have been at play here.

In any case, Hamas was able to begin their attack with the element of surprise. This was aided by an initial early-morning barrage of rocket fire, which was a relatively routine experience for the Israeli garrison forces, but which survivors recall sent most of their number hurrying as a standard precaution into fortified bunkers where – critically – they could not physically observe the approach to the border. They would normally have instead relied on the surveillance cameras to monitor the situation. Hamas, however, used small, off-the-shelf drones rigged with mortar rounds and other explosives to attack and disable the communications towers powering the network. These drones were too small and low-flying for radar to detect, so would have had to have been spotted by eye and ear. Without the cellular data link provided by the towers, the cameras did not function, and neither did the sensors and alarm systems.

With the surveillance and communications systems down, Hamas commandos then used their now infamous paragliders to simply fly over the fence. There they faced little armed opposition. The remote-controlled machine gun emplacements, if they could even operate without wireless data, had also been destroyed by drones. Now isolated, 23 high-tech observation posts each manned by a single soldier – all of them young women – were ambushed and rapidly overwhelmed by the first attackers. Those who tried to report the attacks would have found they couldn’t easily communicate. Meanwhile Hamas used bulldozers and wire cutters to quickly level around 30 sections of the fence without resistance. All of this took only a matter of minutes.

Operational command and control of the IDF division guarding the border had been concentrated into a single centralized base close to the fence. As some 1,500 Hamas terrorists surged across the now open border, this base was quickly overrun and the senior officers there killed or captured. They likely received little-to-no warning, given pictures circulating of scores of soldiers having been shot while asleep in their barracks, many still in their underwear. The subsequent sudden absence of central leadership and breakdown in the chain of command, along with the communications problems, meant that the scope and gravity of the overall situation could not easily be pieced together or communicated to either local forces or to national-level military command. Thus in the end it took hours for leaders to fully grasp what was happening and for reinforcements from elsewhere in the country to be successfully contacted, mobilized, coordinated, and moved to the south to confront the threat.

How should we think about this? At the simplest level, we could say the IDF was overconfident in their defenses and underestimated their enemy, which is clearly true. “The thinning of the forces [stationed near the Gaza border] seemed reasonable because of the construction of the fence and the aura they created around it, as if it were invincible, that nothing would be able to pass it,” recounts Brig. Gen. Israel Ziv, a former head of the IDF’s Operations Division and ground forces commander in the south.

We could also say that they had allowed themselves to become strategically rigid, and were ill-prepared to adapt flexibly in response when things went wrong, which is also true. From the moment the fence was proposed, some military officers had warned that pouring resources into it (along with Iron Dome) was a mistake, because it would ultimately only degrade the military’s overall ability and preparedness to maneuver offensively and preemptively neutralize the enemy’s ability to conduct attacks. Col. Yehuda Vach, commander of the IDF’s Officer Training School, warned in 2019 that, “Because we don’t cross the fence, the other side has become strategically stronger,” as they’d been handed operational initiative. “The enemy will seek in the next campaign to carry out an operation to kidnap soldiers and harm civilians in the towns near the fence, thus enjoying the first achievement of the campaign,” he ominously predicted. “The fence creates an illusion and gives a false sense of security to both the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces and the residents near the fence,” he said.

These are both classic military mistakes, warned against repeatedly by strategists from Clausewitz to Sun Tzu, and made countless times over the course of history. In this case, however, the even greater mistake may have been that the IDF came to rely far too heavily on technological solutions, methods, and ways of thinking.

One of the most famous sayings of the legendary U.S. Air Force pilot and strategist Col. John Boyd, who helped develop modern maneuver warfare (and is maybe best known for inventing the “OODA Loop”) was: “People, ideas, machines – in that order!” While warfighting devices were and are important, as are doctrines, tactics, and stratagems, these are all less important than the people doing the fighting, planning, and organizing – and are far less adaptable and reliable. As Boyd would often harangue Generals in the Pentagon, usually to no avail: “Machines don’t fight wars... Humans fight wars!”

Boyd had seen for himself the perils of overreliance on Big Brain tech wizardry in Vietnam. The latest generation of U.S. aircraft, designed by geniuses who insisted the age of aerial gunfights was long over, had been stripped of their guns and maneuverability and built to be flying missile and bomb platforms. But in combat the missiles proved horrifically unreliable, and they had such a narrow launch envelope they could not be used in a close-in turning fight at all. Moreover the planes themselves no longer had the agility to effectively dogfight. When they ran into light-weight North Vietnamese MIGs, they got creamed. The U.S. air-to-air kill ratio fell from 10:1 in the Korean War to 1:1 in 1967. Boyd himself had to develop and crash-train American pilots in new aerial tactics that could open enough space in a dogfight to make the missiles viable (and he would later be instrumental in ensuring the F-15 and F-16 were designed to actually be effective fighter aircraft). Meanwhile, in the Six Day War of 1967, the Israeli Air Force had devastated the MIGs of their Arab opponents with an aerial kill ratio of 6:1, but every single kill recorded was with guns. Israeli pilots had prudently insisted on keeping their guns, and the requisite skills to use them, as a backup.

While technologies can certainly offer up solutions to discrete problems, these are often fragile solutions. Because technologies are almost always constructed for some specific purpose, with many assumptions built into their design, they are typically not flexible and adaptable enough to function as intended when things go sideways. And the majority of those things that might go wrong cannot be conceived of and planned for in advance. Moreover, if relied upon, technological solutions can produce entirely new liabilities and weaknesses that did not even exist before. In the current case the widespread reliance of the IDF’s defenses on wireless data transmission became a critical weakness that the enemy was able to exploit to great effect.

In fact, it seems likely that Israel was actually even worse off with all its high-tech border gadgetry than it would have been without it. These over-engineered solutions to guarding the border were not cost effective, instead representing an opportunity cost that could have been better spent elsewhere – like on maintaining a much greater number of disciplined, sharp-eyed men with guns. When the tech failed, it was only such men who were able, eventually, to adapt and respond (unsurprisingly, disciplined men with guns were also the decisive factor in those few civilian communities that were able to fight off and survive the attack). Perhaps worst of all, by reversing Boyd’s admonition and putting machines first and people last, the IDF actively degraded the capability of those people to respond to disaster when it most mattered.

But I think even this understates the bigger problem exposed by the folly of the “smart fence.” Israel’s smart-border defenses should be understood as the adoption of a needlessly complex system. Complexity here must not be mistaken to just mean “complicated.” Rather, a complex system is a technical term defining a system composed of such a great quantity of component parts, in such intricate relationships of dependency and interaction with each other, that its composite behavior in response to entropy cannot be predictively modeled. Such systems are characterized by their nonlinearity, feedback loops, and unpredictable emergent properties. When things go wrong in a complex system it can’t be easily solved, because each sub-system relies on many other sub-systems, and pulling any one lever to try to solve one problem will produce totally unexpected effects, potentially only creating more problems. This means complex systems are vulnerable to failure cascades, in which the failure of even a single part can set off an unpredictable domino effect of further failures, which spread exponentially as more and more dependencies fail. Even if the original failure is fixed this cannot reverse the cascade, and the whole system may soon face catastrophic collapse.

This is essentially what happened to Israel’s border defense system. The replacement of low-tech solutions with high-tech ones needlessly added additional layers of complexity to the system, creating new networked points of critical failure that didn’t previously exist. Under pressure, the system then collapsed more completely and with more devastating consequences than if a simpler system had been used. The reliance on overly-complex solutions – when combined with the removal of those legacy elements considered overly redundant but actually most important (i.e. large numbers of troops) – made the system more, not less fragile.

In contrast, simpler systems are often more reliable and robust. Robust systems are ones that can take hits and keep rolling. In the best cases they are not only resilient but actively anti-fragile (they gain from and grow stronger amid disorder). Such systems often have built-in redundancies and alternative, adaptive modes of operation. But often this resilience/anti-fragility isn’t owed just to engineering that attempts to plan for what could go wrong – simplicity itself works its own magic to add to the robustness of systems and strategies. Simple approaches and systems are more cost- and energy-efficient, more intelligible, easier to execute, easier to replicate and scale, easier to adapt on the fly, more self-reliant, less dependent, easier to repair, and less likely to fail under pressure. Simplicity itself can be a serious asset.

This doesn’t mean, to be clear, that I think technology can never be useful or that adding it always produces a net-negative. Obviously the realm of war is a particular example of where technological change has always played a very important role – to my disappointment no army would be able to win today with the cheerful simplicity of the good ole’ sword and shield. But close inspection would I think reveal that those technologies that tend to really work, and ultimately have the most transformative and lasting impact, are almost always those that are the most simple, robust, adaptable, and scalable, and which generally reinforce and work in accord with the human element, rather than attempt to totally replace him with a complex system. The cheap little drones that Hamas used so successfully, and which have also already revolutionized warfare in Ukraine and elsewhere, are a perfect example of this.

But at a broader level, it seems to me that today our tech often seems to be working against us more often than not, precisely because we keep using it to add needless layers of complexity to all our systems. Have you noticed that – to exaggerate only slightly – basically nothing works anymore? The faucets in the public bathroom don’t function because the motion sensors have gone haywire, and apparently manual knobs are no longer a thing. Your new refrigerator or grill comes with a touch screen and a smartphone app, so of course it becomes unusable within a year when some chip gets fried. Your computerized electric car bricks itself in your driveway after downloading a software update, and has to be towed away because it’s impossible to repair. Have any of these things been improved in their function? No, quite the opposite. But they are more complex!

Today we have come to practically worship technology and complexity for its own sake, believing it to be the sorcery that must be able to solve our problems once and for all. Except far too often it actually doesn’t – it just creates the illusion of having done so, while our own capacities have actually diminished and our vulnerabilities to entropy-induced system failure have increased. In this way, technology has increasingly become a false idol, squatting in the place of or even preventing genuine human ingenuity, innovation, and adaptability.

Meanwhile, I fear that we currently also rely on much bigger complex systems than refrigerators, or even smart fences. Civilizations and empires are complex systems too (even they insist on calling themselves a “rules-based international order” or whatever). And empires fall the same way most complex systems do: by becoming too complex to bear their own weight. They come to span the globe, and have too many alliances and commitments, too many dependencies and “vital national interests,” too many IOUs to ever handle at once. Too many expenses; too many sunk costs; too many critical resources and trade routes; too many protectorates; too many enemies… This is what “imperial overstretch” really means: not just that there is too much budgeted for the treasury to pay for, but that overall complexity has reached such a level that the empire has become literally impossible to manage. At that point trying to solve every emergent problems only creates more problems; the empire may still remain strong, but it has become fragile. The potential for even a single point of failure to ignite a catastrophic failure cascade grows more and more acute.

Today, as the United States and its allies rush with increasingly visible panic to try to put out one fire after another around the world, I’m afraid that a global failure cascade may be exactly what we’re witnessing. The number of lights blinking red is growing faster and faster as more dominos fall. The challenge is that if this is the case then even solving existing problems will never be enough: new problems will emerge out of the very logic of the cascade itself, and efforts to fight one fire may just set off new fires. Might America, by embroiling itself in two regional wars at once, prompt China to invade Taiwan when it otherwise wouldn’t have dared, for example? It seems like a possibility. But then we can’t know, on this or any other potential escalatory crisis. Growing unpredictability is now the defining feature of the system.

There are many people who, witnessing this chaos play out, will predictably argue that it is conclusive evidence that the empire needs to redouble its efforts, to yield no ground anywhere, and to show everyone the power of its “global leadership.” The encroaching jungle must be forced back everywhere, they will insist, chopping wildly, because to retreat anywhere would be to demonstrate weakness and invite calamity. Instead, if we want to stave off collapse we must commit to do more. But to do more means to add more complexity to the system, and thus more vulnerabilities. Needless to say, this doesn’t do anything to prevent or stop a failure cascade – it only increases its ultimate scope, momentum, and unpredictability.

Naturally a wiser method would seem to be to simplify: to deliberately pare back commitments and overextended positions, concentrating on conserving strength and defending only the most critical nodes of the system, until the balance of capabilities and commitments can reach a stable new equilibrium. But reform of this kind is extremely difficult, as untangling the imperial Gordian Knot one thread of at a time often proves to be impossible – that’s the problem with complex systems, after all. Which is why historically this type of impasse is typically only ever resolved, and simplicity restored, with one decisive stroke: by systemic collapse.

Maybe that’s happening already, and maybe it’s not. But in any case it seems to me that it might be prudent for many of us to nonetheless start doing what we can to preemptively simplify now – and thus become more resilient and less vulnerable – while we still can do so of our own accord.

For several years I was a principal engineer at Amazon and I was a periodic member of the "availability team" which did post-mortem analysis of every event that caused the web site to go down. Amazon is/was the most operationally competent company I have ever worked for but the scale at which they operated required a level of complexity that no one could really get their arms around. No one fully understood the inter-relationships and dependencies between all the micro-services. The system required intense, continuous automated monitoring to achieve our goals in terms of uptime/availability. (At one point, fully 20% of the entire system's compute capacity was being consumed merely to process faux requests that checked on whether the system was up.) Everything you say about the challenges of complex systems is true. But I will offer a couple of other observations.

First, when faced with complex systems, human beings have a strong propensity to develop superstitious explanations for the visible phenomena they observe. (The last talk I gave to the engineering organization before leaving Amazon was called "Superstitious Architectures: How to Avoid Them".) Prying understanding from complex systems is hard and people are often happy to settle for superstition. (I offer as evidence a lot of what the lay press is saying about AI right now.) What this means in practice is that complexity causes human actors to operate in a state of greater general ignorance. Not a happy circumstance when the sh*t hits the fan.

Second, people are being driven to despair of their own human agency as their dependence on technology they can never understand grows. This is not entirely accidental I suspect and is probably even a little sinister. This has the effect of increasing dependency within the general population and reducing the sum total of initiative in the population at large.

Your advice to focus on simplifying our own lives is wise and even prescient I suspect.

Thanks for this essay.

Excellent essay.

The failure cascade of complex systems is not limited to war. Consider the collapse of Just in Time inventory systems during the COVID lockdowns. One bottleneck proved to be able to shutdown whole industries. A major disaster loomed when the Governor of Pennsylvania shut down all of the rest stops and restaurants along the PA interstates. This effectively cut the major supply line to NYC. President Trump and the President of the Teamsters "explained" things and got the order rescinded.

Going back to the defense of Israel, they had apparently forgotten the failure of the Bar Lev Line in 1973. Technology aside crust defenses are inherently fragile. See also Maginot Line and Great Wall of China. If you depend solely on a crust defense, once the enemy breaks the crust, they have a free run in the vacuum behind the crust. What is needed is defense in depth to contain the attack while larger forces mobilize to drive it back. Especially in an age of terrorism, an armed citizenry is indispensable. Citizens are the targets of terrorism so by definition they are the first to fight. Behind them are police, regional military (National Guard in an American context) and then the regular military.