Is the world about to go bust? Are we at the terminus of a historical cycle, when “the old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born,” as everyone’s favorite Cultural Marxist Antonio Gramsci would put it?

As an internet writer with a penchant for the cyclical and the apocalyptic, I am of course always inclined to answer affirmatively. But I was a bit surprised to see that billionaire investor and Darwinian-capitalist extraordinaire Ray Dalio seems to think so as well.

At least that’s the argument Dalio makes in his new book on the “changing world order,” out today, in which he predicts, based on a study of historical trends in politics, geopolitics, economics, and especially debt, that the shit is about to hit the fan. Or as he puts it more politely: “the times ahead will be radically different” from what almost anyone alive today has experienced, given that the “most recent analogous time was the period from 1930 to 1945.”

Unfortunately, Dalio’s record appears to have been pretty good of late, because he seems to have accurately predicted much of the madness manifesting in today’s economic and financial markets nearly two years ago. I say this because, while his book has just been published now, it’s based on a series of notes to investors (also titled “The Changing World Order”) that together totaled hundreds of pages, and which he later published in abridged form on LinkedIn. (All quotes and charts in this post are sourced from there unless otherwise noted. Since I’ve read these rather than the book, this isn’t exactly a book review, but it doesn’t look like much has changed in the hardcover version anyway.)

Now, I do have to say that I’ve never been the biggest fan of Ray Dalio. The famous financier hasn’t just frequently displayed the libertarian arrogance typical of hedge-funders, but built a culture at his firm that is reportedly so bizarrely totalitarian that it’s been repeatedly described as cult-like. He also has a habit of defending China’s CCP regime with uncomfortable regularity. Still, he is clearly a very smart man who has made a lot of money by predicting global “macro” trends, and is probably worth listening to. And if he’s right, he’s right.

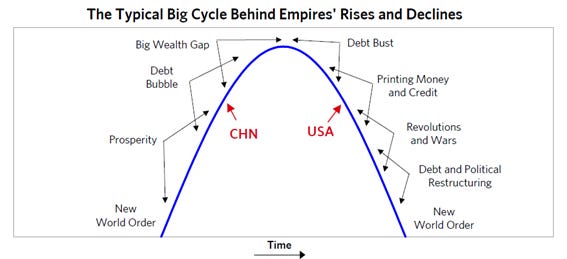

At the core of Dalio’s forecast is an analysis of several interconnected and self-reinforcing cycles that he distills from lengthy historical investigations into the rise and fall of empires, including the Netherlands, Britain, multiple Chinese dynasties, and the USA. From this he derives the theory of a “Big Cycle” that is itself driven by smaller cycles of political, economic, fiscal, and monetary policy mismanagement, all of which tend to drive historical periods of imperial decline, political unrest, conflict, and often the reordering of global power. This Big Cycle tends to manifest itself every 75-100 years in a reliable pattern, and its latest conclusion is, he says, now upon us.

But first let’s take a closer look at each of the cycles he describes.

The Debt and Credit Cycle

Given his profession, Dalio devotes special scrutiny to a cycle of debt/credit growth and collapse that has long bedeviled societies, arguing that it is impossible to understand the sources of national and international political upheaval without grasping this cycle.

At its most basic, debt follows a simple cycle. In a crude summary: people or businesses with money provide other people or businesses with goods or services on the basis of credit – that is, on the promise they will be paid back later. This creates a debt, the sum to be repaid. But one man’s debt becomes another man’s asset, and one man’s business conducted on credit becomes another man’s income, which can become the basis for more credit. Therefore a sum of money has essentially been imagined into existence out of thin air and added to the activity of the economy. Eventually enough people want to be paid back, but can’t be, that debts have to undergo a restructuring – the money can’t all be paid back at once, so debtors do some belt tightening to pay back a portion of the amount owed in accordance with their income, though lenders don’t end up with all the money they expected, or at least as fast as they expected. But since that reduced debt payment was also itself someone’s income, the whole system necessarily undergoes a contraction. This produces a recession of economic activity during a period of adjustment. Then the process begins again, all playing out over the course of a relatively short period of time, about 8-10 years. Dalio calls this the short-term debt cycle, but it is alternatively known in economics as the “business cycle.” And as Dalio puts it, “Most people have seen enough of these short-term debt cycles to know what they are like – so much so that they mistakenly think that they will go on working this way forever.”

But, he argues, such short-term cycles only obscure a much more consequential long-term debt cycle, which takes 50-100 years to play out. That’s because every time the economy sags, thanks to the short-term debt cycle, government – or in the modern era the government’s central bank – intervenes. The central bank typically does so by lowering interest rates, making it cheaper to borrow money, stimulating economic activity. If the economy is running unsustainably “hot,” producing inflation and financial asset bubbles, the central bank will, theoretically, raise interest rates to make it more expensive to borrow, cooling economic activity and encouraging a deleveraging. However, two things typically occur over time: overall debt levels are not cleared away by the short-term contractions and continue to build, while governments’ addiction to faster growth and higher employment means central banks keep rates inappropriately low and so over time loses their capacity to effectively inject further stimulant. At such times those holding debt in the form of government-issued currency no longer see that as a good store of wealth, and consistently seek to exchange it for other assets, contributing to asset price bubbles. Any remaining rate cuts by the central bank do not produce real economic growth, only increased asset prices. Eventually, a short-term cycle will end with very high debt levels and the central bank will no longer have the capacity to easily intervene effectively. At this point “the long-term debt cycle is at its end, and a restructuring of the monetary system has to occur.”

One of two things will then happen. The government can lead a painful adjustment and restructuring process for the whole system in order to return it to sounder footing, cutting its own deficit spending and overseeing a period of severe private sector defaults and bankruptcies, a collapse in asset prices, and likely a temporary economic depression. Or, they can print money.

Printing a lot of money and thereby devaluing the currency is an easy means to wipe out large debts, because the fixed principal of those debts is devalued – a process called “debt monetization.” Since taking bitter medicine is not a winning campaign issue, while handing people money definitely is, politicians have a strong tendency to choose this latter option. Thus, “in virtually all cases the government contributes to the accumulation of debt in its actions and by becoming a large debtor and, when the debt bubble bursts, bails itself and others out by printing money and devaluing it. The larger the debt crisis, the more that is true.”

Dalio stresses that this isn’t necessarily a bad idea. It does function as a means of clearing debt, and if the money that’s printed is wisely used to invest in projects and services that benefit the real fundamentals of national economic productivity (he cites quality education and infrastructure) while combined at the same time with some restructuring and appropriate reforms, then this strategy can work to get a country through a long-term debt crisis intact.

This outcome is rare, however. It requires serious governmental discipline. So more often printing money sets off a chain of very serious consequences. Usually most of the money ends up not channeled into productive projects for the public good, but handed out to favored political constituencies and/or flowing straight to the financial system, boosting asset prices (most benefiting the rich) while causing inflation (most harming the poor). This rapidly exacerbates existing wealth gaps. Higher inequality, inflation, and stagnation or decline of real economic growth lead to political instability, producing populist movements (of left and right). If this instability grows bad enough, it eventually leads to revolution or civil war. Meanwhile, internal turmoil and economic and monetary mismanagement lead to a weakening of the nation’s military strength and overall influence, increasing the risk of external conflict as others look to capitalize on the vacuum created by its weakness. If war occurs, even more money must be printed to fund the conflict.

Finally, if the nation in crisis is an empire powerful enough to have the “exorbitant privilege” of controlling the world’s reserve currency (the currency in which most commerce is conducted, and which people everywhere are therefore forced to acquire to effectively do business), then this will allow them to get away with money printing for a good while (those without this privilege are forced to restructure far more quickly). But, if the final conclusion of the debt crisis is put off long enough, the implosion of the dominant empire’s power through economic crisis and internal and/or external conflict can force a restructuring not only of the state, but of the entire international monetary system, with the reserve currency transitioning, over time, into the hands of a new, more productive competitor.

The long-term debt cycle can therefore be fatal for old and rising nations alike. It takes a very politically competent and well-managed state, and a cohesive society, to navigate through the inevitable crises without suffering significant damage. Typically most states only make it through a couple – or at most a handful – of these cycles, occurring every 75-100 years or so, before succumbing (hence in part why most empires only manage to survive for a couple hundred years, on average). [1]

Unfortunately even those nations that begin as well-run, cohesive, and energetic don’t tend to stay that way for long.

Cycles of National Power and Stability

Contemporaneous with the debt cycle, in Dalio’s analysis nations tend to also go through cycles of competence and competitiveness, as well as cycles of internal political stability, together forming a long cycle of rise and decline. When countries on the downswing of the national cycle simultaneously collide with the end of a long-term debt cycle, the result tends to be bad.

He identifies 17 factors that comprise national strength, from leadership competence, to rule of law, to military strength, with each tending to move along a spectrum from favorable to unfavorable over time, weakening the nation – potentially terminally unless these trends can be turned around in a period of national renaissance.

These factors are not all equal, however. Some must necessarily come first and provide a foundation for growth of national prosperity. Therefore he believes most nations follow an archetypical pattern of rise and decline. Key factors like strong education and innovativeness usually come first, propelling economic competitiveness and productivity. Trade follows, with financial flows closely linked to trade (he stresses that the world’s top trade power has historically always become the center of global finance). Eventually, after it reaches the peak of its power, an empire may gain coveted reserve currency status.

Nations also tend to all decline in the same manner, however. The seeds of poor performance are sowed early as levels of education, competitiveness, and innovation decline, followed by industrial output and trade exports. But other factors, like military strength and financial activity tend to lag significantly, creating the appearance of continuing strength even long after the nation’s foundations of power are hollowed out. Reserve currency status is the last to go, first gradually and then suddenly.

Eventually the empire’s heydays are long gone, with only a mid-tier financial center and a nostalgic global fondness for holding some of its once prestigious currency remaining as a shadow of former glories.

This process of rise and decline is accompanied by a cycle from political stability to instability, forming six archetypical stages of national rise and fall.

In Stage 1, a new internal order has begun, with a new regime having come to power after peacefully or not-so-peacefully replacing the old order and begun working to cohere and consolidate its control over the system, typically by purging all counter-revolutionaries.

In Stage 2, the young regime builds out a new governing bureaucracy and a system for allocating resources, refining both to work efficiently and effectively.

In Stage 3, the system is working well, there is peace and prosperity, and the government enjoys popular support; citizens are proud and enthusiastic about the nation and its direction.

In Stage 4, national enthusiasm leads to great excesses in spending and debt (often along with military overextension), widening wealth gaps and increasing partisan political divides; the bureaucracy becomes bloated and inefficient.

In Stage 5, financial conditions are very bad thanks to the conclusions of the long-term debt cycle, and political tensions are very high; the government – now thoroughly corrupt – is printing money to try to pay its debts and mollify the populace.

In Stage 6, printing money no longer works at all, order has collapsed, and civil and/or external conflict commences; either a new order emerges from the ashes and returns the nation to Stage 1, or it disappears from history.

Usually there is yet another simultaneous cycle going on – the Currency Cycle – with the new regime in Stage 1 often forced to act to restore public trust in the nation’s debased currency by returning to a “hard” currency, such as precious metals (a “Type 1” currency), or at least a paper currency that is directly backed up by hard assets (a “Type 2” currency), before eventually moving to a more easily printable currency backed by nothing but pixie dust, aka a fiat currency (“Type 3”).

Dalio of course goes into currency in far more depth, but in the interest of keeping this brief I will not. (Cypto enthusiasts and skeptics can make their own conclusions and argue about it as they please while we move on).

The Big Cycle

All of these cycles of national decline, when combined with the long-term debt cycle, tend to lead to big changes in international power dynamics, dramatically reshaping the world order along with its dominant values – the process Dalio calls the Big Cycle.

He examines in depth how the Netherlands rose to control the seas and the flow of trade and finance in Europe, before debt crisis, currency debasement, and external and internal conflict weakened the country and contributed to it being surpassed by a rising Britain. British dominance, although longer lasting, would then itself be weakened by the same cycles, until it was overtaken by the United States.

In Dalio’s telling the most recent round of this cycle is the story of what happened in the period from 1930-1945. The stock market crash of October 1929 signaled the end of both the short-term debt cycle of the Roaring Twenties and the long-term debt cycle in multiple countries at once (thanks globalization), but most prominently in the US. The resulting depression resulted in political instability and, with interest rates already low, governments printed money like mad to try to save the economy and quell social unrest. In the US this was successful, with FDR leading a “peaceful revolution” that combined government investment (the New Deal) with forceful restructuring measures and a significant redistribution of wealth. Elsewhere, such as in Germany, it was a disaster, leading to hyper-inflation and the emergence of ideological challengers to the democratic state (communism and fascism). In Germany, Italy, and Japan, fascist movements took control and proved more willing and able than their predecessors to take dramatic action to restore the economy. They would then increasingly challenge the world’s established powers (e.g. France and Britain, who were still struggling despite maintaining their democracies) for geopolitical control, producing World War II.

As the war came to a close, the winning powers convened – most famously at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944 – and established a “new world order” represented by a new monetary system (the “Bretton Woods System” ) in which the money printing came to an end, the US dollar was re-linked to gold (the US then holding 80% of the world’s gold stocks) and many countries’ currencies were pegged to the dollar (the US being the most productive and stable economy). This created an American-dominated global financial system, with the US dollar soon replacing the British Pound as the global reserve currency. With confidence in the monetary system restored, business boomed. The former European great powers were relegated to decline into mere normal countries, while the US became the world’s foremost superpower.

Where We Are Now

Times have changed since 1945, however. Just over 75 years later, the debt cycle has had a chance to run its course again, even as the US became less competent, less productive, and less united. Then came the 2008 financial crisis. In Dalio’s view, this was the decisive moment of our era. Like 1930, it marked the end of the long-term debt cycle and the beginning of a critical transitionary period. The US Federal Reserve, with rates already near zero, reacted with “quantitative easing” – aka printing money – and never stopped. Then the arrival of the pandemic sent the printers into overdrive.

The debt bubble is reaching unprecedented heights, though not only in the United States. The overall global debt-to-GDP ratio is now above 356%, well beyond the 280% reached before the 2008 crash. Monetizing the debt probably look increasingly attractive in Washington. A tide of fiat money has pushed asset prices to record highs. Inflation has mysteriously emerged from nowhere. The gap between rich and poor grows ever greater, while political divides grow ever more rancorous. Foreign competitors smell opportunity and grow restless with anticipation of a new order.

In Dalio’s view there are now basically two options. The United States can pull itself together, invest its printed money wisely, restructure its debt, reform its system, and address its inequality and political divides. Or it can succumb to the national cycle, plunge into civil conflict, and be overtaken by China, which will found the future “new world order” (at least until it has to reckon with its own cycle, anyway).

Dalio is actually very worried about war between the US and China occurring as the latter threatens to overtake the former (he devotes a whole chapter to this). But he seems to think there’s a good chance we will do ourselves in before this comes to fruition anyway.

“The United States is now in Stage 5,” he says, though we have “not yet crossed the line into Stage 6 (the civil-war stage).” Are we destined to reach it? “Judging by the indicators the honest answer is that it is too close to call. Hardly anyone expects that the US will cross the line to have a civil war/revolution, though it could,” he reassures us. “History shows us that civil wars inevitably happen,” he says, so “rather than assuming that ‘it won’t happen here,’ which most people in most of the countries assume after an extensive period of not having them, one should be wary of them and look for the markers to indicate how close to one one is.” (Although, yesterday Dalio specified that there is only “a 30% chance” of a “major civil-war type conflict,” so don’t panic.)

How will we know we’re experiencing the death throes of the republic? We’ll be able to see it if, politically, “reason is abandoned in favor of passion,” and “playing dirty is the norm” as “winning becomes the only thing that matters.” And if, late in Stage 5, “there are increasing numbers of protests that become increasingly violent” as “demonstrations start to push the limits of revolution.” Or, if it becomes “common for the legal and police systems to be used as political weapons by those who can control them,” while paramilitary “private police systems form—e.g., thugs who beat people up and take their assets, and bodyguards to protect people from these things happening to them.” These are all very bad signs. Once people start dying in pitched street battles, you’ll know it’s probably on.

In the end Dalio helpfully advises that “periods of civil war are typically very brutal,” so, “That brings me to my next principle: when in doubt get out. If you don’t want to be in a civil war or a war, you should get out while the getting is good. History has shown that when things get bad, the doors typically close for people who want to leave.”

Ok thanks for that Ray, I’ll just take my golden visa and head for my bunker in New Zealand now then.

A Very Brief Assessment

There are quite a number of things I could quibble with about Dalio’s analysis. I think his view of China’s inevitable rise and the relative brilliance of its leadership (there is a whole chapter on this) is deeply rose-colored. I’m not sure his pattern of how nations develop is really accurate (education and free trade are not magic pills, as any number of economists have pointed out). His whole theory is somehow simultaneously deeply Marxist in analysis and his proposed solutions mostly neo-liberal. There is almost no analysis of culture’s role in stability or instability to be found here (except regarding China’s alleged superiority), only economic factors. I think his take on populism being a universal ill is not only terribly simplistic, but not even in accordance with his own critique of wealth concentration and government corruption…

But in the end I don’t think I know enough to really make an argument in opposition to his core thesis. On the contrary, it seems to be rather common sense to me. Its message may just be something, like so much in today’s world, that people tend to ignore because they don’t want to hear it. So while I may not head for the exits quite yet, I will take Dalio’s warnings to heart and go long on canned beans.[2]

In the meantime, the whole book is a strong reminder for me to dig deeper into the economic and finical elements of our global upheaval, and I look forward to doing more of that here in the future.

If you liked this and found it helpful please feel free to forward it to a few people and encourage them to subscribe!

[1] Interestingly, Dalio suggests that the Biblical command to enact a debt jubilee [forgiveness] every 50 years (Leviticus 25:8-13), as followed off-and-on by Judeo-Christian states historically, served as a pragmatic method for short-circuiting the long-term debt cycle by pricing-in regular debt clearance in a way that markets could prepare for rationally, helping to effectively stabilize the system.

[2] This is not certified financial advice. Invest in beans only if doing so is in accordance with your personal risk tolerance for legumes and overall financial outlook.

My biggest question is the extent to which demographics will play any role in China's further development. Some suggest robotics and AI will continue to drive development forward; others note that the dependency ratio and weak social safety net will be a drag on the country, and that it will undergo a Japan-style stagnation before it gets wealthy. That, of course, could also create instability--note the past writing on "bare branches" in China, meaning unmarried men, and the suggestion that that would lead to social unrest and perhaps a more aggressive foreign policy. I'm not a demographer or an economist so I can't speak to these with any insight.

Please continue to dig deeper into the financial and economic elements of our global upheaval.

"In Dalio's telling the most recent round of this cycle is the story of what happened in the period from 1930-1945."

I have been often telling my wife over the past 5 years that it looks more and more likely that we will now have the "delightful" opportunity to probably experience some new configuration of those previous 15 years of chaos/instability/war that ran from 1930 to 1945.

On this economic/financial front also keep an eye on the writings of Adam Tooze--especially his now ongoing weekly chartbook series.

I would call Tooze (a brilliant historian) an emerging Keynesian political/economic reformer, who seems to be hopeful that some type of new global financial/economic package similar to Bretton Woods might still be fashioned, through U.S. leadership, using a a more dramatic mobilization of state-sponsored government spending as the major tool in bringing about national and international political stability.

Also on the economic/financial/political front don't ignore the anthropological/economic analysis of the late David Graeber. From my perspective he offers an extremely articulate critique of more traditional left state-centricity that is implicit in some of the ideas of Tooze.

And finally, as I have previously mentioned, keep on eye on the Paul Kingsnorth series on the mega-machine--especially his ideas on technology, culture, and the use of the covid crisis to accelerate authoritarian tendencies.

Kingsnorth also offered a powerful critique of Keynes in his "What is the Acid," essay where he notes how naive Keynes was in his assumption that when a society cores itself around avarice and usury it could suddenly drop such vices when some plateau of Keynesian economic perfection might be reached.